Many people find insects annoying, even frightening. As a former fruit fly geneticist who spent many boyhood years exploring insect and other life in the swamps near my home in Leamington, Ontario, I’ve always been fascinated by them. They’re also a critical component in the web of life.

When insects are killed or die off, everything in the food web is affected, from the birds, bats and lizards that feed on insects to the snakes, coyotes and cougars that feed on birds and lizards, and on and on.

We haven’t learned our lesson over the 63 years since was published — a book that influenced me and others and was the inspiration for growing environmental awareness. Carson pointed out the folly of applying new technologies or scientific developments on a widespread scale without understanding or even considering the impacts on interconnected natural systems.

Before Carson’s book, Swiss chemist Paul Mueller developed the pesticide DDT and won a Nobel Prize for his work. It was seen as a miracle chemical, deadly to many “pests” and disease-carrying insects. It’s use on malaria-carrying mosquitoes saved many human lives, but it also led to the deaths of millions of bald eagles, osprey, pelicans and other birds. Carson learned that, beyond having a direct impact on animals that feed on insects, especially birds, DDT was also “” in some species and “biomagnifying” through the food web, including to humans.

Insecticide bans helped insect populations recover in some places, but they now face another dire threat: global heating. Many scientists believe insect biomass is being reduced by as much as 2.5 per cent a year. That may not seem like a lot. “But if you run that forward just four decades, we’re talking about nearly half the tree of life disappearing in one human lifetime. That is absolutely catastrophic,” entomologist .

Pesticides (still), habitat loss, industrial activity, agriculture, and air, land, water and light pollution are still eradicating insects, but new research points to climate disruption as an increasingly devastating factor. Insect populations are now plummeting even in areas free from pesticides, fertilizers and industrial activity — including protected forests in countries such as Costa Rica. Many insects are hypersensitive to environmental changes — in heat, humidity, rainfall, light and seasonal variations. Events such as an unusually dry spring can prevent them from emerging from the ground, for example. Availability of water is especially critical, as they must stay constantly hydrated.

Insect collapse is already working its way through the web of life. A 2019 study found that in the U.S., close to one-third, had disappeared since the 1970s, mostly those that feed on insects. A found a significant decrease in birds, frogs and lizards as insect numbers dropped.

Because many insects are pollinators, their decline can also reduce plant and food crop growth.

Anyone who’s been around for a while might remember road trips of the past, when you’d have to stop regularly to and grill. Now, their numbers have diminished to the point that you can often drive a long way without a single splatter.

It’s hubris. We fail to understand that nature, which includes us, is interdependent, that every disruption or disturbance we create will have far-reaching consequences. And so we spray poisons indiscriminately, wastefully burn fossil fuels and destroy natural spaces and habitat. But if insects die, birds and fish that eat them will die and animals that eat the birds and fish will also die...

We have numerous solutions to these problems — to climate change, biodiversity loss (including insects) and pollution — but sometimes it means putting life before profit, and that doesn’t sit well with those who make their money from polluting fuels and chemicals.

We must do everything we can to protect insects. That includes addressing climate disruption by shifting to clean energy and conserving and restoring green spaces. Individually, we can with native, pollinator-friendly plants, and fertilizer use .

It’s time to show our insect friends some respect. in more ways than most people know.

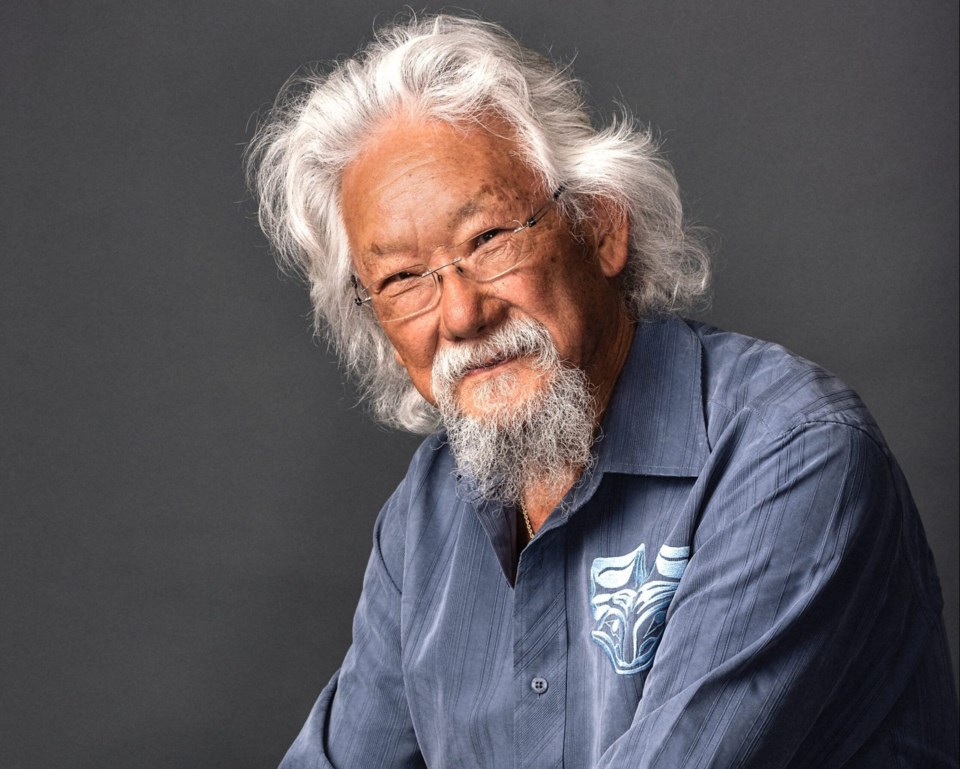

David Suzuki is a scientist, broadcaster, author and co-founder of the David Suzuki Foundation. Written with David Suzuki Foundation Senior Writer and Editor Ian Hanington.

Learn more at .